# The Apollo 13 Mission: A Remarkable Journey of Survival and Ingenuity

Written on

Chapter 1: The Launch and Initial Challenges

The Apollo 13 mission embarked on April 11, 1970, marking 50 years since its historic flight. This event is often dubbed “history’s most successful failure.”

On that fateful day, Apollo 13 launched from Cape Canaveral, as part of the third mission aimed at landing humans on the Moon. However, less than six minutes into the journey, complications began to arise.

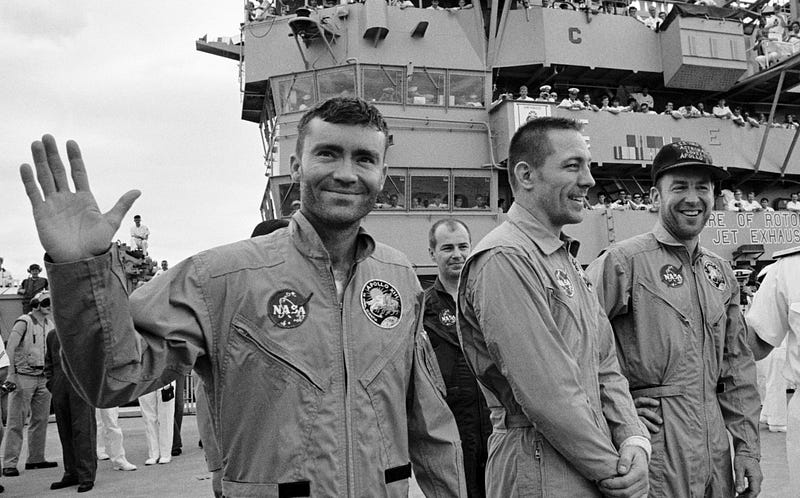

For six days, a global team of engineers and scientists scrambled to rescue the Apollo 13 crew—John Swigert, Fred Haise, and Commander James Lovell, who had previously orbited the Moon during Apollo 8. The astronauts displayed exceptional resilience, ensuring their survival amidst the challenges that threatened not only their lives but also the future of the Apollo program. Through a combination of technological expertise and quick thinking, both ground teams and those aboard the damaged spacecraft turned a dire situation into a story of triumph.

The crew of Apollo 13 aboard the USS Iwo Jima after their harrowing mission. From left to right: Fred Haise, John Swigert, and James Lovell. Image credit: NASA

Trouble for Apollo 13 began even before its launch. Just days prior, backup lunar module pilot Charles Duke inadvertently exposed the crew to German measles, leading to the replacement of command module pilot Ken Mattingly with John Swigert, who was immune.

Additionally, ground tests raised concerns about a poorly insulated helium tank in the Aquarius lunar module (LM), which was used for landing. Originally part of the Apollo 10 capsule, this tank had been modified but was accidentally dropped during installation. While external inspections showed no visible damage, internal components had loosened, setting off a chain reaction that would jeopardize the mission. Further complications arose when heating elements in the tank sustained damage as engineers attempted to remove excess liquid oxygen.

In a bid to address these issues, the astronauts were instructed to board the lunar module three hours ahead of schedule for tank testing.

11 April 1970 19:13:00 (UTC) — Liftoff

The liftoff of Apollo 13 was flawless. However, within two days, the focus would shift from landing on the Moon to ensuring the crew's safe return. Image credit: NASA

Initially, the launch appeared to proceed smoothly, but catastrophic events were looming. For the first 48 hours, the mission was relatively uneventful.

Key Events During the Launch

11 April 19:18:30 — Premature Engine Cutoff

At 5.5 minutes post-liftoff, the center engine of the S-II stage shut down prematurely, causing the remaining engines to burn longer than anticipated.

11 April 19:25:39 — Earth Orbit Insertion

The crew achieved Earth orbit at an altitude of approximately 190 kilometers (120 miles) and completed one and a half orbits before setting their sights on the Moon.

13 April 01:53:49 — First Mid-Course Correction

About 30 hours into the mission, the command module Odyssey and lunar lander Aquarius made their first planned course adjustment, setting them on a trajectory toward the Moon—a destination they would ultimately never reach.

At 46 hours and 43 minutes after launch, the capsule communicator (Capcom) at mission control reported everything was normal.

“The spacecraft is in real good shape as far as we are concerned. We’re bored to tears down here,” he said.

Despite this optimistic report, the mission, aimed at landing on the Fra Mauro region of the Moon, was about to turn into a desperate fight for survival.

On April 14, the crew participated in a live TV broadcast, showcasing life in microgravity. However, public interest in the Apollo program was dwindling, and this broadcast went untelevised.

The Calm Before the Storm

At 55 hours and 46 minutes after liftoff, Lovell concluded the broadcast with a polite farewell, unaware that chaos was just moments away.

14 April 03:05:58 — LOX Stir Command

When mission control instructed Swigert to stir the oxygen tanks, it marked the last routine task the crew would perform before disaster struck. The oxygen tank began to heat, and all safety protocols failed.

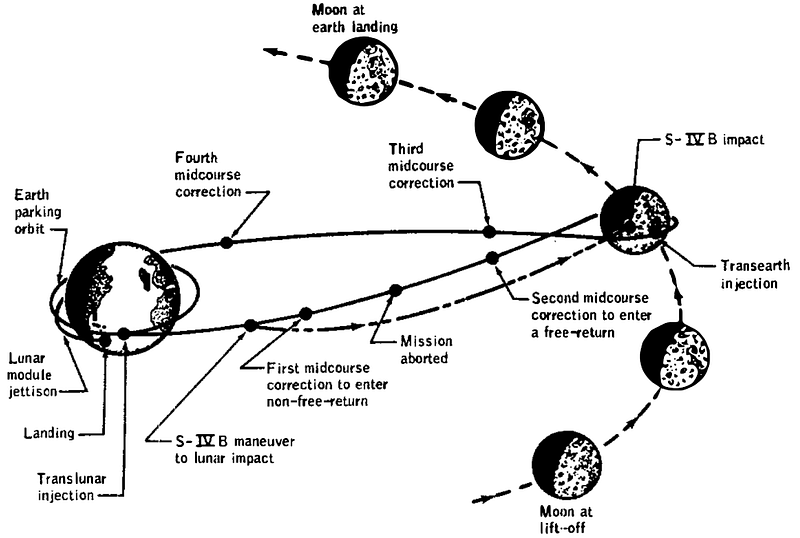

The position of the spacecraft relative to Earth and the Moon as the crew reached various mission milestones. Image credit: NASA

14 April 03:07:00 — Explosion

“Commander Jim Lovell and LM Pilot Fred Haise were completing a system check of Aquarius when they heard a significant bang,” NASA recounts. This loud noise signaled the explosion of the number two oxygen tank.

The explosion led to a critical loss of power, light, and water aboard the craft. The crew found themselves in a perilous situation, over 322,000 km (200,000 miles) from Earth.

In a move reminiscent of submarine protocol, the crew closed the hatch between the command module and the LM to contain the air supply. However, the hatch didn’t seal correctly, compelling the astronauts to secure it manually.

14 April 03:08:20 — “Houston, we’ve had a problem here”

Seeing alarming warning lights, Swigert transmitted the now-famous phrase, “Houston, we’ve had a problem here.”

The situation rapidly deteriorated. The second oxygen tank was completely empty, and the first tank was losing oxygen fast. Additionally, two of the three fuel cells responsible for the capsule's power had failed.

Thirteen minutes following the explosion, Lovell noticed flakes drifting outside the window.

“We are venting something out into space… It’s a gas of some sort,” he reported.

What Lovell observed were remnants of their dwindling oxygen supply escaping into the void.

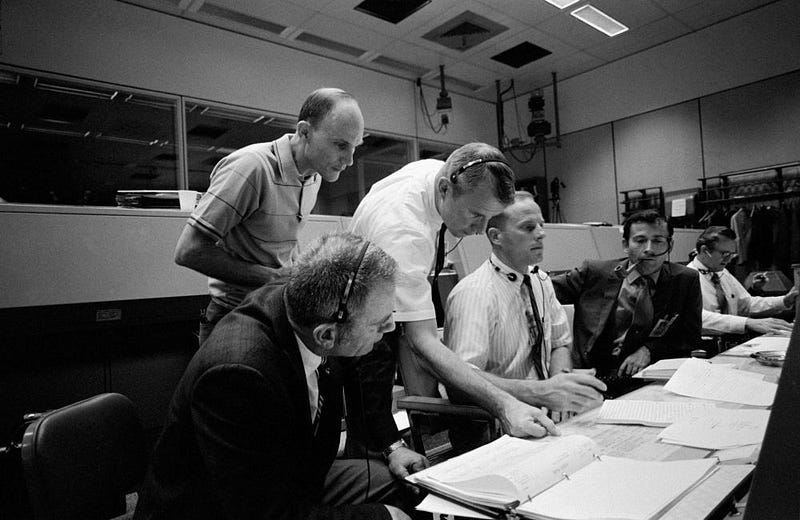

NASA’s ground team, including engineers and astronauts, worked tirelessly to devise a plan to save the endangered crew. Image credit: NASA

As oxygen supplies dwindled, the astronauts realized they would have to leave the command module and move to the LM for survival.

14 April 05:53:00 — Command Module Power Down

With only 15 minutes of power left in the command module, NASA ordered the crew to transfer to the lunar module, which was now their only hope for survival.

Commander Jim Lovell in the lunar module as temperatures dropped in their makeshift lifeboat. Image credit: NASA

The LM, while originally designed for a 45-hour mission, had sufficient oxygen to sustain the three astronauts for over 90 hours, which was crucial for their safe return. However, electricity was scarce. The LM batteries held 2,181 ampere-hours, but all non-essential systems were powered down to conserve energy.

Water supplies were critically low, with initial estimates predicting depletion five hours before re-entry. However, previous missions indicated that systems could function for up to eight hours without water cooling.

The crew was restricted to only six ounces of water per day, significantly less than their usual intake, supplemented by fruit juices and moist foods.

NASA engineers quickly formulated new procedures to navigate the crew back to Earth safely.

14 April 08:42:43 — Second Midcourse Correction

The spacecraft, initially aimed for a lunar landing, was now redirected for a safe return to Earth. A 35-second burn set them on a free-return trajectory, which utilized the Moon’s gravity to assist their return.

15 April 02:40:39 — Trans-Earth Injection

A day and a half after taking refuge in the LM, the crew received another alarming warning. Despite the breathable oxygen, carbon dioxide levels were becoming dangerously high.

Although lithium hydroxide canisters were available to scrub the air, they were designed for the command module and incompatible with the LM’s system. Ground teams quickly devised a solution using available materials to create makeshift adapters, buying the crew valuable time.

A visual representation of the Apollo 13 crew’s journey around the Moon, racing back to Earth. Image credit: NASA

On April 16, at 04:31:28, the crew fired their engine for five minutes, significantly reducing their return time. This maneuver also adjusted their landing site closer to the US naval recovery fleet.

While orbiting the Moon, the crew executed one of the few scientific tasks of the mission, directing the third stage of the Saturn V rocket into a collision with the lunar surface, aiding researchers calibrate lunar seismometers.

17 April 12:52:51 — Fourth Midcourse Correction

The navigation systems onboard the LM were not equipped to handle the calculations necessary for their return. Typically, these calculations would be managed by the Odyssey's systems.

Astronauts would have relied on a sextant to locate a navigation star; however, debris from the explosion hindered their ability to do so. Instead, they turned their attention to a much closer star—the Sun.

Once aligned with the Sun, they could safely execute another midcourse correction, accelerating their journey back to Earth.

As they drew closer, temperatures plummeted to as low as three degrees Celsius (38 Fahrenheit), making rest nearly impossible. Moisture condensed on every surface of the spacecraft.

Final Steps Toward Home

17 April 16:43:00 — Lunar Module Jettison

Four hours before landing, the crew re-entered the Odyssey command module. Despite concerns over moisture affecting the control panels, safety measures implemented after the Apollo 1 tragedy minimized risks.

The Apollo 13 service module separates from the spacecraft in preparation for re-entry. Image credit: NASA

The crew detached the service module, revealing a panel blown out from the earlier explosion. Three hours later, they released the lunar module Aquarius, which had served as their lifeboat, before entering Earth’s atmosphere on April 17 at 17:53:45. As the command module heated up, moisture inside began to condense, creating rain within the cabin.

17 April 18:03 — Splashdown

The Apollo 13 crew successfully splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, near Samoa, and were promptly rescued by the USS Iwo Jima's crew.

Apollo 13 crew members exiting their capsule to safety on life rafts. Image credit: NASA

During this extraordinary mission, the crew confronted immense challenges, including severe temperature conditions that led to significant weight loss—31.5 pounds collectively among the three astronauts, with Jim Lovell alone losing 14 pounds.

The explosion resulted from a series of errors and miscalculations. The voltage allowed for the oxygen tank heaters had been increased without updating the switches. A critical test left one switch on too long, causing heat buildup that damaged the Teflon insulation.

Jim Lovell reading a newspaper about their safe return. Image credit: NASA

“[D]amaged insulation around electrical components in the Command and Service Module’s (CSM) second oxygen tank caused an electrical short that led to the explosion. The short ignited the oxygen and insulation material, resulting in a rapid pressure buildup that destroyed the tank and endangered the crew,” reports The Planetary Society.

Thermostatic switches that should have opened were likely stuck shut, and warning signs were overlooked as the oxygen tank overheated for eight hours, ultimately leading to the explosion 200,000 miles from Earth.

Throughout the Apollo 13 mission, the crew traveled 622,268 miles over five days, 22 hours, 54 minutes, and 11 seconds. The mission showcased NASA's capabilities and became a defining moment for the space agency.

In the aftermath of Apollo 13's remarkable journey, the intended landing site at Fra Mauro was repurposed for Apollo 14's touchdown.

James Maynard, founder and publisher of The Cosmic Companion, resides in Tucson with his wife Nicole and their cat, Max.

Did you find this article insightful? Join us on The Cosmic Companion Network for our podcast, weekly videos, informative newsletters, and updates on Amazon Alexa and more!