Understanding Brain Plasticity and the Purpose of Dreams

Written on

Chapter 1: The Dynamic Nature of the Brain

Brain plasticity refers to the brain's remarkable capacity to adapt and reorganize itself as we engage with our surroundings. In "Livewired: The Inside Story of the Ever-Changing Brain," neuroscientist David Eagleman delves into profound questions, such as the implications of living with only half a brain and the reasons we dream.

Traditionally, we tend to perceive brain regions as fixed entities, each dedicated to specific bodily functions. However, the reality is much more fluid. At birth, we possess basic neurons that are not entirely preordained. As we interact with our environment, our brain’s wiring adjusts based on sensory feedback and physical movement.

Eagleman offers a fascinating analogy:

Imagine instead of dispatching a four-hundred-pound rover to Mars, we send a tiny sphere that can fit on the tip of a pin. This sphere utilizes energy from its surroundings to replicate into numerous similar spheres. These spheres connect and develop features like wheels, lenses, and sensors, eventually forming a sophisticated internal navigation system. Witnessing such a phenomenon would be astonishing.

Wouldn’t it be incredible if we could replicate such technology? A mechanism that mirrors our brain's functionality.

Chapter 2: The Case of Half a Brain

Consider the scenario of a six-year-old losing half of their brain. Initially, one might expect the corresponding side of the body to be paralyzed, perhaps even affecting speech. However, astonishing recovery can follow.

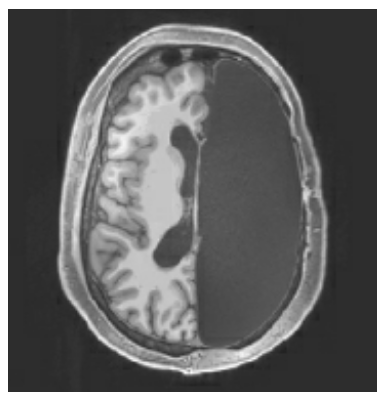

Take, for instance, the story of Matthew. After suffering frequent seizures over three years, he was diagnosed with Rasmussen’s encephalitis, a condition affecting an entire hemisphere of the brain. The only solution at that time was a Hemispherectomy, resulting in a fluid-filled cavity where half of his brain once was.

After just three months of therapy for both physical and language skills, Matthew returned to his prior developmental level. Years later, he leads a typical life, experiencing only a slight limp and limited use of his right hand. This remarkable recovery occurred because his brain rewired itself, with each half taking on functions typically assigned to both sides.

A similar case is that of Alice, who was born with only the left half of her brain. Surprisingly, this was undetected until she was three and a half years old when she experienced minor seizures. Thanks to medication, Alice enjoyed a normal childhood.

Eagleman presents another insightful analogy about the brain's adaptability.

Imagine the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic. If a tsunami devastated the Dominican Republic, one possibility is that Haiti would continue unaffected. Alternatively, the Haitians could expand their territory to accommodate the displaced Dominicans, showing extraordinary generosity and cooperation.

Chapter 3: The Science Behind Dreaming

Notable musicians like Ray Charles and Stevie Wonder, who lost their sight, demonstrate how the brain compensates for lost senses. When a person becomes blind, the visual cortex becomes less active, allowing other areas, such as those responsible for sound and smell, to expand. This results in heightened sensitivity in these other senses.

Once we understand how the brain reorganizes after losing a sense, one might wonder about the speed of these changes. The answer is remarkably quick.

Researcher Alvaro Pascual-Leone investigated this phenomenon by blindfolding sighted participants for five days while they practiced reading Braille. Each day, they showed improvement, and brain scans revealed that even their visual cortex activated during tactile tasks. Remarkably, once the blindfold was removed, their brain reverted to its original state within a day. This illustrates the brain’s incredible ability to reorganize itself rapidly.

However, there is more to discover. In another experiment, participants were blindfolded while performing various tactile tasks, and it was observed that brain reorganization could occur in as little as 40 to 60 minutes.

Given the brain's rapid adaptability, it’s proposed that dreams serve as a protective mechanism. When we sleep, our visual cortex is at a disadvantage since it cannot engage with the external world. To safeguard this area from being overshadowed by other senses, the brain generates internal imagery, allowing us to "see" with our eyes closed.

Eagleman succinctly summarizes this theory:

"We propose that dreaming exists to keep the visual cortex from being overtaken by neighboring areas."

Final Thoughts

Thank you for exploring the fascinating topic of brain plasticity with me. The intricacies of our brain's adaptability are nothing short of awe-inspiring. Learning about the underlying reasons for dreaming, rather than just the content of our dreams, has shifted my perspective. While this theory remains unproven, it offers a compelling explanation for a complex phenomenon.

Reference:

(affiliate link)

Livewired: The Inside Story of the Ever-Changing Brain

Livewired: The Inside Story of the Ever-Changing Brain [Eagleman, David] on Amazon.com. FREE shipping on qualifying…

amzn.to